The Three Tiers of Government

Now and then, the question arises about whether we need three levels of government. We have federal, state, and local governments, but do we need the three? It is essential to go back to why the three levels came to be before deciding if we need them.

Historical Background

Australia’s journey towards becoming a federation began in the late 19th century. Before this, the continent was divided into six separate British colonies: New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia, and Tasmania. Each colony operated independently, with its own government and laws. The idea of uniting these colonies into a single nation gained momentum in the 1880s and 1890s, driven by the need for a unified defence system, a standard immigration policy, and the desire for economic integration.

One point worth noting is that names like South and Western Australia are based on geography. Victoria, Queensland and New South Wales are all derived from English colonisation. Tasmania is named after a Dutch explorer from the 1600s. None of them reflect the Aboriginal origins.

Taxation before Federation

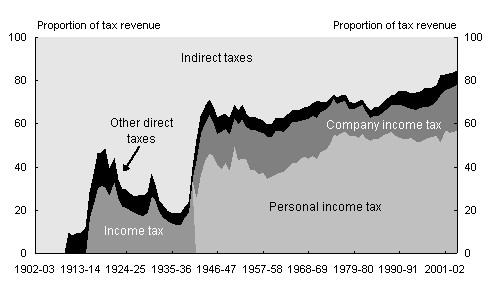

Before Federation in 1901, each colony administered their own tax system, with excise, customs duties and income taxes as the primary sources of tax revenue. There was an excise tax on trade between the states. Income tax represented a relatively small proportion of tax revenue.

Federation and the Birth of States

The push for federation culminated in drafting the Australian Constitution, which was approved by the British Parliament and came into effect on January 1, 1901. This marked the birth of the Commonwealth of Australia, a federation of states. The six colonies became the six states of Australia, each retaining its own government and certain legislative powers. The Constitution established a federal system of government, dividing powers between the federal government and the states. It also did away with taxes between states.

The Concept

The original thinking was that the Federal Government would be responsible for areas that were outward looking and the States would be more internally focused. The States collected 80% of the taxation revenue and forwarded a small proportion to the Federal Government.

Taxes

As mentioned, income taxes were a small part of the overall tax system, but in 1915, the Federal Government instituted a Federal Income Tax to fund the war effort. Both State and Federal Governments collected income tax up to 1942, which resulted in inconsistencies across States.

The Second World War saw significant changes to the tax system as State Income Tax was absorbed into the Federal Income Tax, and States relied on Federal Grants to replace the lost revenue. New Government funding for things such as unemployment relief and widows’ pensions during the 40s meant more tax had to be collected. Income tax was about 4% of GDP at the turn of the century but had risen to 22% by the Second World War.

Federal Government Income by Type

As the demand for more goods and services to be provided by the government increased, taxation also increased. The world was moving away from protected industries after WW2, and trade barriers, including tariffs, were being removed. Australia lagged badly during the 50s under the assumption that we must preserve local industries at all cost.

Imported goods were subject to massive import duties, resulting in Australians paying much higher prices for cars, TVs, food, clothing and raw materials than other countries. Australian companies could not produce on the scale of overseas companies, so their prices were higher. Importers could have brought in cheaper goods of the same quality, but when tax was taken into account, the goods became more expensive.

By the mid-20th century, the proportion of taxes had flipped. Initially, the federal government collected 20%, but now they collected 80%. States had to survive on stamp duty on housing purchases and a range of smaller taxes. Some were replaced or terminated when GST was introduced as a tax collected by the Federal Government and handed back to the States.

The third tier, Local Government, was left to survive on Federal and State Government handouts and rates imposed on residents within the council area.

The three tiers play games of cost shifting, where one body tries to push expenditure to another body. The health system is a prime example of the Federal Government trying to get people out of the NDIS and onto State Government-funded schemes.

Responsibilities

Something like Defence or Immigration lends itself to a Federal approach, but what about Education or Health? On the surface, there should be a single approach across the States to how we educate our children or deliver health services, but education is a state responsibility, and health is divided between the two. Would having a single entity responsible for education not be more efficient? Do we need to create the same syllabus in every state?

Here, we return to a question at the heart of the whole mess. What would be left for the states if all the things that should be centralised were managed by the federal government?

What if it was Today?

Here is a thought experiment. Imagine you were setting up a government system today. You start with a Federal Government and give them responsibilities. Would you create State Governments? If there were no existing States, how would you define boundaries? Would they be as big as current states or smaller? Would they be structured on a city-country divide where some were only cities, and others only country?

More importantly, what would states be responsible for? Managing local services such as roads and rubbish? That is what the 500 local Councils do. Where would they get their revenue? Do they get an allocation from the Federal Government?

Now, another experiment. What if State Governments performed the duties of Councils? Instead of each council having a contract for rubbish collection, there is a State Government contract or contracts. Instead of councils needing all the staff and equipment to repair roads in their area, there is a State pool of equipment and people. Rather than navigate conflicting council rules for development, there is a single set of state requirements.

When you look at the situation through this lens, it is hard to see any reason for three tiers of Government. Efficiency and removal of duplication point at one central government.

To reinforce this view, here is a personal experience from a few decades back. I was asked to assist a State Government department in investigating how to build a new computer system to manage their assets. During the early discussions with senior bureaucrats, they mentioned that another state had built a very effective system to manage their assets. The assets were similar, so I asked the obvious. Why don’t you use the same system the other state had built, and you can jointly maintain and develop it?

I was greeted with astonished looks. Of course not. We would never do that. We build and maintain our own systems. We might talk to them about how the system works and what difficulties they have had but never use their system.

Benefits of Three Tiers

Inertia cannot be the only reason for three tiers to exist. There are other reasons;

- Checks and balances. Instead of one body having all the power, decisions are made in one place and subject to review and amendment in another. Federal governments set some building regulations, which are filtered through state government regulations and are finally subject to council regulations. While it is called ‘red tape’, it limits what governments can mandate.

- Local representation. Electing state or council politicians gives voters a person closer to their issues and more likely to be influenced by what people in the region want.

- Surburban protection. Councils are expected to maintain the status quo or only approve changes that benefit most local residents. No high rise in my street, NIMBY prevails. Someone around the corner I can call when the grass is not mowed in the local park or there is a pothole outside my house.

- Diversity. What is appropriate for a city may be inappropriate for a country town. One size does not fit all. There is the risk that if there is one central government, they will impose a system that will not work in some places.

Alternative Model

An alternative model is having a central government manage all revenue collection and allocation and turn the regional government bodies into delivery mechanisms.

Imagine there were regional management bodies. We currently have eight states and territories and over 500 councils. Imagine if we had 200 or 300 regional bodies that were delivery arms of the central government. Each had its own budget and was tasked with delivering outcomes in whichever way worked in that region. The central government provides a generic way to offer services, and the regional body adapts the process to suit the local community’s needs.

There are a million reasons this would not work, but is it worth investigating if the system could be adapted? Are there objections that could be resolved? Are all the problems insurmountable? What are the costs, and what are the benefits?

Conclusion

If you look at the Western World today, and the USA in particular, much of the reason for turning to a disruptor like Trump is the frustration of not seeing progress from the Government. Unless we do something about it, democracy will grind to a painful halt. People will become so disillusioned with democratic government inaction that they will walk away from democratic principles.

The model above may never work. There is probably a much better model floating about, but nobody is game to talk about it because too many people are invested in the existing system. The only way we can start the generation-long process of changing three tiers of government is to start thinking about it now. Next time you hear someone complain about red tape, ask them how they would reorganise government. Their answer may surprise you.