Progressive Patriotism

Prime Minister Albanese has started using the term “Progressive Patriotism” as a concept for governing the country. What is it?

Progressive. Adjective. 1 – Happening or developing gradually or in stages.

2. (of a person or idea) favouring social reform.

Patriotism. Noun. The quality of being patriotic; devotion to and vigorous support for one’s country.

Patriotism is different from nationalism. Nationalism is defined as identification with one’s own nation and support for its interests, especially to the exclusion or detriment of the interests of other nations. Nationalism is patriotism with aggression towards other countries. Trump, Putin and Netanyahu are nationalists, not patriots.

To combine the two, “Progressive Patriotism” is to develop social reform for the country and ensure that the majority of Australians support the reform.

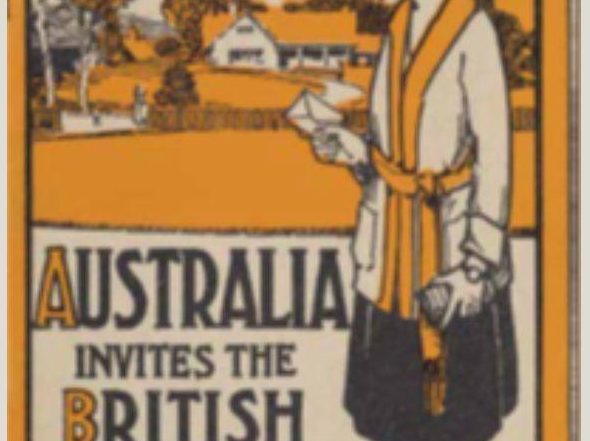

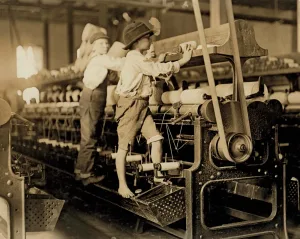

So, let’s talk about social change. About two centuries ago, in the Western world, we had child labour. Women didn’t have the vote, and in many countries, only landowners participated in elections. Schooling was optional, and health services barely existed. The wealth divide was much greater than it is today.

Attitudinally, the various churches ruled supreme. If you were not white, you were inferior. Abortions were illegal and often lethal. Homosexuality was covered up, and anyone identified as gay was openly persecuted. Equality across sexes, classes, and positions was not even considered something to pursue.

The question is, what happened to change all those social norms?

Society has many differences, but one difference between individuals is the propensity to accept change. We are like a flock of sheep being moved to new fields. Some are out in front, keen to get to greener pastures. The “eager frontrunners”. They believe the grass is greener on the other side of the hill and cannot wait to get there. At the back are the “laggards” who can only think about how this paddock is not quite as green as the last paddock. The ‘laggards” would be happy to turn around and go back to the start.

If left to their own devices, the flock will no longer exist. At the starting point will be the “laggards”. At the end, there will be the “eager frontrunners”. In between will be a flock scattered from start to finish, and probably wandering off in other directions.

Here is an example of evolving social change. Look at child labour laws in England over a century.

18th Century: Little to No Regulation

- Early Industrial Revolution: Children as young as 5 or 6 worked in textile mills, mines, and as chimney sweeps.

- No laws existed to limit the age of employment, working hours, or conditions.

- The use of pauper children from workhouses as indentured labourers in factories was commonplace.

19th Century: Progressive Legal Reforms

1802 – Health and Morals of Apprentices Act

- The first law targeting child labour.

- Applied only to apprentices in cotton mills.

- Limited working hours to 12 hours per day.

- Some basic education and cleanliness standards are required.

1819 – Cotton Mills and Factories Act

1819 – Cotton Mills and Factories Act

- Prohibited employment of children under 9 years old in cotton mills.

- Limited working hours to 12 per day for those aged 9–16.

- Poorly enforced, due to a lack of inspectors.

1833 – Factory Act

- Major turning point.

- Banned the employment of children under 9 in textile factories.

- Ages 9–13: max 48 hours per week (8 per day).

- Ages 14–18: max 69 hours per week.

- Required two hours of schooling daily.

- Factory inspectors were appointed for the first time.

1842 – Mines Act

- Prohibited underground work for:

- All women

- Boys under 10

- Response to reports on harsh mine conditions.

1844 – Factory Act

- Lowered maximum working hours for children 8–13 to 5 hours daily.

- Further strengthened regulations and inspection.

1847 – Ten Hours Act

- Limited working hours for women and children (13–18) to 10 hours daily.

- Applied to textile mills.

1870 – Education Act (Forster Act)

- Established framework for elementary education.

- Made education compulsory for children aged 5 to 13, though enforcement varied.

1878 – Factory and Workshop Act

- Consolidated earlier laws.

- Set the minimum working age at 10.

- Required children to attend school until age 10.

- Applied to more industries, not just textiles.

1891 – Elementary Education Act

- Raised compulsory school leaving age to 11.

- Further curtailed child labour.

It took 100 years to reverse child labour. What drove the change was:

- Public pressure and reform movements.

- Investigative reports (e.g., by Lord Shaftesbury).

- Growing belief in the importance of education and child welfare.

In other words, over 100 years, there was a change in how the public saw child labour, through government reports, and through a new perception that children needed to be educated, and that children should have rights.

I am sure there were “eager frontrunners” in 1800, and they started chipping away at the block, but the “laggards” took a century to catch up.

Imagine what would have happened to national cohesion if the 1891 Elementary Education Act had been passed in 1791, not 1891. Businesses would have been crying that they would be ruined. Ninety per cent of the population would have seen it as government meddling in their lives. Protests would have filled the streets. Social cohesion would break down. In any case, where is this education going to come from? Where are the schools, and where are the teachers? Where is the money?

In this case, and in many other cases, the flock must be kept moving together. Not at the speed of the “eager frontrunners” and not at the speed of the “laggards”. The former needs to be slowed down, and the latter sped up. Moving too fast or too slow brings social disruption.

Today, we face a different set of social changes to address. In 100 years, we will hopefully have addressed climate change issues, energy availability, free dental cover for all, pre-school funding, housing prices, and water availability. It may take decades for these to all come to fruition.

Arguing for these changes goes through six stages.

- Identification of a problem by the “eager frontrunners”.

- The “eager frontrunners” typically propose a solution that may not necessarily be the most practical.

- The “laggards” deny a problem and raise the issue of “what will it cost, and where does the money come from. The middle of the flock is usually divided about the problem and the solution, and is generally apathetic.

- Gradually, sometimes over decades, the middle moves to accept the problem, and that there needs to be a solution, but not how we pay for it.

- Over time, the government will find a way to pay through increased or redirected taxes, and legislation will be proposed.

- Eventually, the majority of the country accepts the solutions.

During this process, the Government tries to slow down the “eager frontrunners” and drag the “laggards” forward. The reason is to keep the flock together. To stop the fragmentation of society. They will make incremental changes, let the public adapt to each before moving to the next change.

You might note that I have not used the terms “conservative”, “liberal”, or “progressive”. These terms like “left” and “right” have too many preconceived connotations. That is why I named those with more conservative views “laggards” and those with more progressive views “eager frontrunners”.

I believe the PM meant this when he coined the term “Progressive Patriotism”. He was trying to avoid preconceptions. He talked about incrementally moving forward at a pace that will keep society together. Keep the flock moving forward without some rushing ahead and some falling behind. It seems a sensible goal for a government interested in national unity.