The Limitations of the U.S. Federal Electoral System

How long can an electoral system fulfil its purpose? The US system has been going for over 230 years. Are the conditions that led to the structure relevant today? Do changes due to social, technological and legal norms mean the electoral process should also change?

Back in 1789, when the first US election was held, America was still recovering from the Civil War. There was little trust between states and their federal counterparts. There was no TV or Internet, so many electors didn’t know the politicians. Communications were primitive by today’s standards. Rather than a united states, they were a very divided states.

The United States’ federal electoral system remains riddled with structural flaws that undermine participation, fairness, and trust. Designed to balance power between states and protect against tyranny, many of its features have become obstacles to equal representation. Key limitations include weekday voting, partisan control of electoral boundaries, decentralised administration, and the separation of powers between the president, the Senate, and the House, which often produces gridlock.

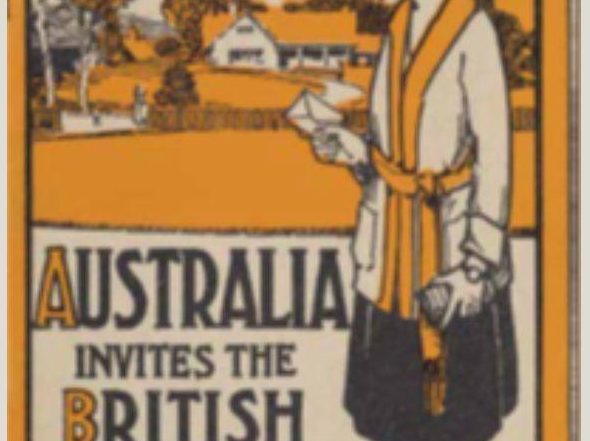

In contrast, Australia’s system, which is just over 100 years old, seems more relevant. It is administered by the independent Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) and offers a more equitable and transparent model.

Here are some of the key differences.

- Tuesday Voting and Voter Accessibility

One of the most enduring peculiarities of the U.S. system is voting on Tuesday, a practice dating back to 1845. Congress fixed Election Day as the Tuesday after the first Monday in November to accommodate 19th-century farmers who needed time to travel to another town to vote after Sunday church and before Wednesday market day. The world has changed, but this anachronism remains. This schedule is now a significant barrier to participation.

One of the most enduring peculiarities of the U.S. system is voting on Tuesday, a practice dating back to 1845. Congress fixed Election Day as the Tuesday after the first Monday in November to accommodate 19th-century farmers who needed time to travel to another town to vote after Sunday church and before Wednesday market day. The world has changed, but this anachronism remains. This schedule is now a significant barrier to participation.

Because Election Day is not a public holiday, most Americans must vote before or after work. Long queues, limited polling stations, and restrictive hours discourage turnout, particularly so among low-income workers and those without flexible schedules. Turnout in U.S. presidential elections rarely exceeds 60%, and in midterms it can fall below 50%.

Australia’s approach is much more accessible. Federal elections are held on Saturdays, and voting is compulsory. The AEC provides postal and early voting options, ensuring near-universal participation. Turnout consistently exceeds 90%, demonstrating how administrative design can enhance rather than hinder democracy.

- Partisan Control and Gerrymandering

Perhaps the most infamous weakness of the U.S. system is gerrymandering—the manipulation of electoral district boundaries to favour one party. Because the Constitution leaves election administration largely to the states, redistricting is usually done by partisan state legislatures. Dominant parties (Republican or Democrat) redraw congressional boundaries to entrench their power, producing irregularly shaped districts that dilute the votes of opposition supporters or minority groups.

It fosters political polarisation by creating “safe seats” where candidates cater to their party base rather than the broader electorate. The Supreme Court’s 2019 ruling that partisan gerrymandering is a “political question” beyond judicial review effectively left the practice unchecked.

Both parties have been responsible for changing boundaries, and even today, states like Florida are recasting electoral maps to add five new Republican seats. California has responded by holding a referendum to suspend its independent boundary-setting system to gain five new Democratic seats.

In contrast, Australia’s electoral boundaries are drawn independently by the AEC. Redistributions for the House of Representatives occur regularly to reflect population shifts and must meet strict criteria for enrolment equality, community of interest, and geography. Public submissions and objections are invited to ensure transparency. This impartial process has effectively eliminated gerrymandering and preserved confidence in fair representation.

- Fragmented Administration and the Lack of a Central Authority

The U.S. electoral system operates across three tiers of government (federal, state, and local), creating extreme fragmentation. Over 8,000 local jurisdictions manage registration, polling, and counting, with wide variation in voting technology, identification laws, and deadlines.

The Federal Election Commission (FEC) regulates campaign finance but does not run elections. This decentralisation breeds inconsistency and confusion: different states use different machines, ballots, and even rules about when votes can be counted. Administrative errors or partisan officials can delay results or erode trust, as seen in Florida’s 2000 presidential recount and other contested elections.

Australia’s AEC, by contrast, is a single, independent statutory authority that conducts all federal elections and maintains the national electoral roll. Its uniform procedures, professional staff, and legal independence ensure consistent standards nationwide. Voters anywhere in Australia experience the same process, reinforcing confidence and legitimacy.

- The Electoral College and Representation

The Electoral College, which elects the U.S. president, is another structural weakness. Each state receives electors equal to its congressional representation, and nearly all States allocate these on a winner-takes-all basis. If there were three senators in a state, and two were Republicans and one was a Democrat, the members of the Electoral College would vote all Republican.

The origins of this go back to the formation of the Constitution. The Electoral College is often described as the last option left standing. Some wanted the person who received the most votes to be President. Others wanted one vote per state. The slave states wanted a fixed number of delegates, determined by each state’s population. It suited them because a black person was counted as 3/5 of a person when determining the state population.

The origins of this go back to the formation of the Constitution. The Electoral College is often described as the last option left standing. Some wanted the person who received the most votes to be President. Others wanted one vote per state. The slave states wanted a fixed number of delegates, determined by each state’s population. It suited them because a black person was counted as 3/5 of a person when determining the state population.

In the end, it was decided that a number of knowledgeable and responsible people from each state, elected in districts by voters, would meet to nominate where their votes would go for the President.

This means the national popular vote does not decide the presidency: candidates can lose the popular vote but still win through narrow victories in key states, as occurred in 2000 and 2016. The system amplifies the influence of small and swing states while marginalising others, and it discourages third-party participation.

Australia’s preferential voting system for the House of Representatives avoids these distortions. Voters rank candidates by preference, and a candidate must secure an absolute majority of seats (50% + one vote) to win. The Senate’s proportional representation ensures smaller parties gain seats in line with their statewide vote share. Both systems, administered by the AEC, ensure outcomes that more faithfully reflect the national will than America’s state-based mechanism.

- Voter Registration and Disenfranchisement

In the U.S., voter registration is essentially a personal responsibility. Each state sets its own procedures and deadlines, which can occur weeks before an election. Millions of eligible citizens fail to register in time or are purged due to strict ID laws or database errors.

Some states permanently disenfranchise people with a criminal conviction, even after they complete their sentences. These rules disproportionately affect minorities, the poor, and the young—groups already underrepresented in politics.

In Australia, the AEC maintains a centralised, continuously updated electoral roll. Registration is compulsory and can be completed easily online or by mail. The AEC updates enrolments automatically using data from other government agencies. Coupled with mandatory voting, these measures ensure participation rates near 100% of eligible citizens—an inclusiveness far beyond the American experience.

- Campaign Finance and Political Influence

The influence of money in U.S. politics is profound. Following Citizens United v. FEC (2010), corporations and wealthy individuals can spend unlimited sums through “Super PACs (Political Action Committees),” often without full disclosure. Campaigns now cost billions, giving major donors and lobby groups outsized influence over policy and candidate selection. The result is an electoral environment dominated by financial power rather than civic equality.

The influence of money in U.S. politics is profound. Following Citizens United v. FEC (2010), corporations and wealthy individuals can spend unlimited sums through “Super PACs (Political Action Committees),” often without full disclosure. Campaigns now cost billions, giving major donors and lobby groups outsized influence over policy and candidate selection. The result is an electoral environment dominated by financial power rather than civic equality.

Australia’s campaign finance system, while imperfect, is far more restrained. The AEC monitors donations and spending and requires public disclosure of significant contributions. In the near future, we will move to real-time disclosure of donations and limits on donations from each individual. Political advertising must include an authorisation statement, identifying who paid for it. If, for example, a mining compay wants to support one party, they must identify that the ad is the product of a mining company. People can draw their own conclusions about the message’s bias. The scale of private money is far smaller, helping maintain public trust and a more level playing field.

- The Separation of Powers and Legislative Gridlock

Another major limitation lies in the division of powers between the executive and the legislature. In the U.S., the President, Senate, and House of Representatives are all separately elected, often with differing political majorities. Because legislation must pass both houses of Congress and be signed by the president, divided government can lead to prolonged stalemates.

The Senate filibuster compounds this problem. Most legislation requires 60 votes out of 100 to advance, allowing a minority to block bills indefinitely. The result is frequent gridlock, where pressing national issues—such as healthcare, immigration reform, and gun control—languish for years despite public support. The system’s design, meant to encourage consensus, often results in paralysis and frustration.

The regular Government Shutdowns are a current example of this. The Congress will not authorise lifting the budget cap, which means the country cannot increase its debt. Despite Trump’s claims of being a successful businessman, he doesn’t see an issue with not paying down debt.

Australia’s parliamentary system provides a stark contrast. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are drawn from and accountable to the House of Representatives, ensuring alignment between the executive and the legislature. A government with a majority can implement its policies swiftly, while the Senate, elected by proportional representation, functions as a genuine house of review. Because minor parties often hold the balance of power, legislation is refined through negotiation rather than being blocked outright. The Australian model, therefore, balances efficiency and accountability far more effectively than the American separation of powers.

Conclusion

The U.S. federal electoral system is showing it’s age. It suffers from design flaws that erode participation, representation, and effective governance. Tuesday voting, partisan gerrymandering, decentralised administration, restrictive registration laws, the Electoral College, financial influence, and institutional gridlock combine to create a system that too often frustrates the will of the people.

Australia’s model, centred on the independent Australian Electoral Commission, demonstrates the power of impartial administration and coherent design. Through compulsory Saturday voting, impartial boundary-setting, transparent rules, and an integrated parliamentary structure, Australia achieves both legitimacy and efficiency.

Ultimately, democracy is not only about citizens’ right to vote. It is about the institutions that ensure those votes are equal, counted, and translated into effective government.

The world changes over centuries and even decades. What was suitable a few centuries ago may or may not be suitable today. Australia’s electoral system is not perfect, but it offers lessons the United States might do well to consider.