Over Time and Over Budget

Why does every project, be it infrastructure, home building or service delivery, end up over budget and over time? That is the wrong question. The real question is this. Why do the initially estimated budget and timetable always end up understated?

It is all about project uncertainty. Projects have several interrelated components.

Scope. What is being built, delivered or created. For example, an infrastructure project may deliver a new rail line, a few tunnels and several stations. An IT project may include a program to manage the financial activities and the hardware to support that software. A health program may consist of staff, facilities, equipment, training, and an ongoing management structure.

Scope. What is being built, delivered or created. For example, an infrastructure project may deliver a new rail line, a few tunnels and several stations. An IT project may include a program to manage the financial activities and the hardware to support that software. A health program may consist of staff, facilities, equipment, training, and an ongoing management structure.- Cost. The program’s scope determines its cost. There are several caveats to that statement. If it involves resources to work on the project, there may be significant variation depending on external factors. A big infrastructure project may be able to attract workers easily unless other big projects are underway at the same time. That could drive up costs.

- Resources. How many people do you need? What skills are required? Can you find people with those skills? Do they fit within your budget?

- Time. Time is a combination of scope, resources and cost. If you are building something, can you throw more resources at it and speed it up? Do you have the money to do that? Are there resources available? Do you build it in one stage, or deliver it in stages progressively?

- Quality. This is often the cause of angst both during and after a project. The top quality will almost certainly require the most money and the longest time, not to mention the best resources. How far back from “perfect” are you prepared to step?

- Risk. There will be risks in a project. How do you manage or mitigate those risks? For example, a construction that spans winter in a rainy area is likely to experience delays due to rain. Do you build potential delays into your schedule and budget or assume you will be lucky? For an infrastructure project involving a tunnel, do you drill core holes to check the earth stability before developing a budget, or do you cross your fingers and hope for the best?

In addition, a project manager has to manage two other components.

- Communication. Ensuring everyone is aware of the information needed to do their job. If there is a problem with the delivery of windows in a house, the people doing the inside walls need to know they will be delayed because the house is not at the lock-up stage. No point in putting up walls if water comes through the window holes.

- Stakeholder Management. The project manager needs to manage all the different parties involved in the project. For a government infrastructure project, it could include government ministers and officials, contractors, suppliers, residents, users of the infrastructure, and the press.

The Funnel

Estimating a project is like a funnel. At the start, it is wide and open. As it progresses, the boundaries become closer and more constrained. Building a train line starts with all sorts of options for the trains themselves, the route, the signalling, where stations are to be located, and a thousand other variables. Each decision will impact cost, time, and scope.

As time progresses, those variables become decisions and consequently, the time, cost and scope tighten. The problem that most people ignore is that it takes time to make all those decisions. People expect the time and scope to be determined on day one. It will never happen.

Imagine a straightforward decision on our hypothetical train project. Do we tunnel below a section, or run the lines on the surface? Making a decision might involve conducting geological surveys, assessing land acquisition, consulting residents, developing cost estimates, assessing the availability of tunnelling machinery, and a hundred other factors. If it took six months to make the decision, the cost of that one part remains unknown for those six months. Only when that decision is made can we estimate the price of the dependencies—the station (above- or below-ground), traffic patterns, interchanges, safety factors, etc.

Estimating the cost by investigating the options is a project in itself. Each option examined affects other decisions, so the whole project has to be planned before we can even get close to an estimate.

One project that is held up as a model was for an airline. They wanted a new ticketing system. It took 14 months of planning to decide whether to buy a commercial software system or build their own. They looked at who would be using it and how it would be used. Did it interface with other systems, and what hardware would be required? After 14 months, they had a plan that included the cost, scope, and time. It came in on schedule, cost what was in the budget and delivered what was required. The 14 months of planning and design led to the system being built in 10 months. It may sound counterintuitive, but the planning can take longer than the build time.

Politics

Governments are in power for only 3 or 4 years. Infrastructure, defence and other projects can run for a decade or more. Governments want to impress the public with their grand plans, so they are keen to announce things as soon as possible. In other words, before all the hard work is done to decide what is to be built, how, when and how much it will cost.

Planning

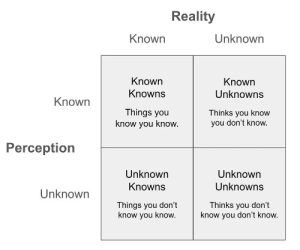

At the beginning of translating an idea into a project, there are four categories.

- Known Knowns. The things you already know about the project. It will be a bridge, a railway line, a three-bedroom house, or a new Naval ship.

- Known Unknowns. It is not hard to find what you don’t know. What sort of bridge? What stations will be on the railway line? Will it be a one- or two-story house? How many sailors will you have to cater for?

- Unknown Knowns. Perhaps there was already a geological study on the bridge or railway line a decade ago, and it needs updating. Maybe there are council-approved plans for a house that could be adapted to the proposed build. An overseas naval group might have a study on options for the warship that they are willing to share.

- Unknown Unknowns. Most dangerously, there are all the things you don’t know, but don’t even realise you don’t know. The toxic soil you will find during excavation. The fires in Canadian forests destroyed much of the US timber supply, driving up global prices. And then, there was Covid.

Politicians are not interested in waiting for all these facts to be assembled. They could be facing an election, and they want this project to help them win.

Optimism

Most people are naturally optimistic about projects. They assume nothing will go wrong and that it will all happen automatically. The thing about projects is that one delay can have a domino effect.

A delay to windows going into a house means the electricians cannot start the following week. The electricians have multiple other jobs, so they may not be able to get back for a month. That delays the gyprockers and the plumbers, who are also not just standing by ready to jump when asked. The whole schedule has to be reorganised.

A delay to windows going into a house means the electricians cannot start the following week. The electricians have multiple other jobs, so they may not be able to get back for a month. That delays the gyprockers and the plumbers, who are also not just standing by ready to jump when asked. The whole schedule has to be reorganised.

For some reason, people looking at infrastructure, IT, or transportation projects think it will all run smoothly. It is a form of irrational, blind faith that nothing will fail.

Risk management is one tool to try to alleviate some of the pain. If there is a risk that the windows will not arrive on time, what can we do about it? Perhaps, to mitigate the risk, we have half delivered early so that one section of the house can be locked up and work can continue. Alternatively, structure contracts with penalty clauses for critical actions.

Contracts

There is a mentality we all have to take the lowest price. Get three quotes and run with the cheapest. Companies responding to tenders are well aware of this. They will structure a tender so that it is low-priced but offers options to expand once it is in place.

Imagine a new computer system is the subject of the tender. The tender is accepted, including hardware, but on closer inspection, it is found that the hardware cannot be expanded. The hardware specification has to be revised. Initially, security systems were not included in the tender, but it became evident that the existing systems were inadequate. There goes another tender variation.

A tender for a navy frigate has accommodation for 50 sailors, but the people providing the communication system want more room for their equipment. They want to take it from accommodation, so other areas have to be used for accommodation.

Conclusion

The question is not how projects run over time, cost and budget. The question is: why do we expect an accurate budget to be developed on day one? The alternative is to fix time and cost and say, build the railway line as far as you can for this amount of money and in this time. Obviously, that is ridiculous.

What we should be comfortable with is an announcement that a project might take between 8 and 12 years and could cost 5 to 10 billion dollars. In a year, we will narrow that number and make decisions on the available options. After another year, we will be within ±20 %.

If we hear an estimate on day one, run and hide. It is in no way realistic.