Treaty Now

The Aboriginal band Yothu Yindi recorded their biggest hit in 1991. It was called “Treaty”. I doubt most people (me included) really understood the context of the song, other than that it was about a treaty between Aboriginals and those who are not Aboriginal.

To really understand, we need to go back long before Captain Cook and the First Fleet. We need to understand the British colonial model.

Exploration was always a mix of three things: Trade, Conquest and Religion. If we go back to the first true national explorers, the Portuguese, they were primarily driven by religion and Trade. Portugal was a Catholic country, and its people believed they needed to spread the religion to every part of the known and unknown world. They were missionaries intent on proving which God was the best God.

Alongside this, they were intent on breaking the monopoly of the spice trade. Instead of spices coming overland on the Silk Road, and from India, they wanted to travel around the tip of Africa, and trade for spices in the East Indies. They were not much interested in Conquest. They were happy to trade with the inhabitants of the East Indies.

The Spanish, on the other hand, were about Religion and Conquest. They invaded South America and ruthlessly exploited the Aztecs and Incas to the point of annihilation. They preached their version of Catholicism and, at the same time, wiped out existing civilisations.

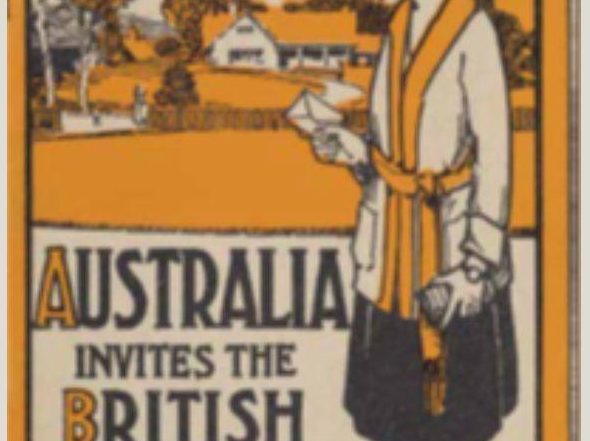

Britain was into Trade and Conquest as well. First, the Americas and Canada, then India and later Africa. Their model was based on invading a country, then drawing up treaties with the indigenous people, giving them limited rights in return for accepting English sovereignty.

Between 1664 and 1667, in America, the English signed the Treaty of Albany with the Iroquois Confederacy. It included alliances on trade in return for peace agreements. The process was to arrive, set up an outpost, prove the superiority of English military power, capture land, and, when the enemy was weakened, draw up a treaty with the native people. In return for land, trading rights, and control of the country, we promise not to kill you anymore.

In 1758, the colonies and 13 Indigenous nations signed the Treaty of Easton to secure neutrality during the French & Indian War. By Royal Proclamation in 1763, the colony recognised Native rights west of the Appalachians. That lasted until gold was discovered, then treaties were conveniently forgotten.

In Canada between 1725 and 1779, several peace and friendship treaties were signed between the British Crown & Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, and Passamaquoddy tribes. They recognised peace and coexistence, but there were no large-scale land cessions. In 1763, by Royal Proclamation, there was recognition of indigenous land rights, and only the Crown could purchase land.

In Canada between 1725 and 1779, several peace and friendship treaties were signed between the British Crown & Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, and Passamaquoddy tribes. They recognised peace and coexistence, but there were no large-scale land cessions. In 1763, by Royal Proclamation, there was recognition of indigenous land rights, and only the Crown could purchase land.

A year later, in 1764, the Treaty of Niagara was signed to reinforce the Proclamation and continue alliance-building. From 1871 to 1921, 11 treaties were signed with different tribes, resulting in vast land cessions in exchange for reserves, annuities, and promises of aid.

In India, the Treaty of Allahabad was signed in 1765 between the East India Company & Mughal Emperor. It gave the company trading rights in Bengal. During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, various treaties were signed by multiple Indian states, in which local rulers retained their thrones but ceded military/diplomatic power to the East India Company. The Treaty of Lahore was signed in 1846, ceding territory and influence to England.

Treaties were signed in the Caribbean in 1739, as well as in Fiji, Solomon Islands, Kiribati, and Tuvalu, among others, in the Pacific during the late 19th century. They gave sovereignty to England in return for peace. Treaties were signed in many African nations between 1800 and 1900, which covered protectorates and annexation. All these defined the role and land access of the indigenous people.

Even in New Zealand, the Treaty of Waitangi was signed in 1840 with the Māori ceding sovereignty but retaining chiefly authority. Nothing like this happened in Australia. Why?

When Cook came to Australia in 1770, his orders were:

“You are also, with the consent of the natives, to take possession of convenient situations in the country in the name of the King of Great Britain, or, if you find the country uninhabited, take possession for His Majesty by setting up proper marks and inscriptions, as first discoverers and possessors.”

“You are to cultivate a friendship and alliance with them, making them presents of such trifles as they may value, inviting them to traffick, and showing them every kind of civility and regard, but taking care never to offend them or, if they give you just cause, to punish them in a manner that may not by any means lead them to a quarrel or bring on a war.”

How the admiralty thought the natives would consent to having their land taken away remains a mystery. Cook took the second option. He decided the country was uninhabited and took possession, raising the English flag on Possession Island (22 August 1770). Cook declared the entire east coast of Australia as British territory in the name of King George III, despite it being inhabited. He justified this by treating the land as terra nullius (“nobody’s land”), although that exact legal doctrine was only applied explicitly much later.

From Cook’s perspective, there were no towns, no Kings or obvious hierarchy, and the people seemed to move about without any permanent residence. He considered them nomadic, and they just passed through the coastal regions. To him, the land was not inhabited.

In reality, there was a clan and tribal structure. There were leaders. There were tribes responsible for specific areas, and although the people did move about, they had a form of agriculture completely alien to the English. They planted yams and harvested them next time they passed through. They burned certain areas to encourage grass to grow, which attracted kangaroos that they would kill at a later time. They even built sophisticated fish traps using arrangements of rocks. None of these were familiar to the English farmers, much less to English sailors.

No treaty.

The First Fleet arrived. Governor Philip started to understand that the people were less nomadic than Cook believed. He had been told to build friendly relationships with the Eora people.

He began moving towards a treaty, but who would sign on behalf of the natives? The English could not communicate with the Aboriginals initially, and in any case, perhaps up to half of the natives died from smallpox, which they had never experienced before.

The Aboriginals avoided the white men, so Philip decided to capture some natives to learn their language and customs. In November 1788, he captured Arabanoo and another man, but they died of smallpox by May 1789.

On 25 November 1789, Phillip ordered the capture of two more men. Marines seized Bennelong (about 25 years old, of the Wangal clan) and Colbee (chief of the Gadigal). Both were taken to the settlement at Sydney Cove and kept under guard.

Colbee escaped after about a week. Bennelong remained for several months, learning English words, dining at the Governor’s table, and developing a wary respect for Phillip. He eventually escaped in May 1790.

In September 1790, Phillip went to Manly Cove, where Bennelong and a large group of Eora were gathered. During this meeting, Phillip was speared in the shoulder (likely as payback for past abductions). Despite the injury, Phillip ordered no retaliation. This act helped establish a fragile peace, and Bennelong later resumed friendly relations with the colony. Bennelong became a key cultural go-between, helping Phillip communicate with Aboriginal groups, but there was no treaty. Phillip even built him a small hut on the eastern point of Sydney Cove.

In September 1790, Phillip went to Manly Cove, where Bennelong and a large group of Eora were gathered. During this meeting, Phillip was speared in the shoulder (likely as payback for past abductions). Despite the injury, Phillip ordered no retaliation. This act helped establish a fragile peace, and Bennelong later resumed friendly relations with the colony. Bennelong became a key cultural go-between, helping Phillip communicate with Aboriginal groups, but there was no treaty. Phillip even built him a small hut on the eastern point of Sydney Cove.

When Philip finished his term and returned to England, he took Bennelong and another Aboriginal man, Yemmerrawanne. In London, Bennelong was presented at court to King George III and dined with English high society. He and Yemmerrawanne were lodged at Eltham under the care of William Waterhouse’s family. Sadly, Yemmerrawanne fell ill and died in May 1794, aged about 19. It is unclear if Bennelong raised the issue of a treaty, but in the two years he lived in England, he must have seen that if the English had decided to take the country, he needed a document to protect his people.

In 1795, Bennelong returned to Sydney aboard the Reliance with the new Governor, John Hunter. By this time, the colony had changed, and Bennelong no longer enjoyed the same status as he had with Philip. Additionally, he had lost status with his own people. He retired from his political/liaison role, probably disappointed that he had spent two years in England and not been able to negotiate a treaty.

It was another five years before a successor to the position of Aboriginal liaison emerged in the form of Bungaree. Hunter, King, Bligh and Macquarie dealt with Bungaree on matters pertaining to the Aboriginals. There was still no mention of a treaty. Aboriginals had little in the way of rights.

They had no rights to land or votes. It was not until the latter half of the 20th century that they were even recognised. In 1948, they were allowed Australian citizenship. Ironic as they had not granted the colonists citizenship. In 1962, they were allowed to vote. In the 1967 referendum, over 90% of Australians voted “Yes” to:

- Allow the Commonwealth Government to make laws for Aboriginal people (previously a state power).

- Include Aboriginal people in the national census.

In 1976, Prime Minister Gough Whitlam passed the first law to legally recognise Aboriginal land ownership in Australia.

During the following decades, information came out regarding the stolen generation of Aboriginal children taken from their parents and raised in orphanages or adopted by white families. This led to the Apology to Stolen Generations by Prime Minister Kevin Rudd in 1997.

From the first colonisation by Britain, there was a refusal to define the rights of the native population. Minor changes occurred over the subsequent 250 years, but it has been an incremental creep forward. Do we need a treaty today? That is a complicated question. To answer the question we need to think about what might be in a treaty. Here are a few items.

- Recognition and Sovereignty

- Acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Nations of Australia.

- Recognise that sovereignty was never ceded and set a foundation for coexistence between two systems of law and culture.

- Land and Country

- Return of certain Crown lands to Aboriginal custodianship.

- Protection of sacred sites, waterways, and cultural landscapes.

- The rights to manage national parks and conservation areas jointly.

- Legal guarantees of land and sea rights beyond the Native Title system.

- Self-determination and Governance

- Recognition of Indigenous nations or groups as self-governing entities in certain areas.

- Support for Indigenous parliaments, councils, or decision-making bodies.

- A framework for consultation on laws and policies affecting Indigenous people.

- Cultural Rights

- Protection and revival of languages.

- Recognition of cultural practices, ceremonies, and law.

- Guarantees for Indigenous-controlled education, media, and cultural institutions.

- Resources and Compensation

- Financial settlements or compensation for dispossession.

- Revenue-sharing from the use of land and resources (mining, fishing, forestry).

- Long-term funding for housing, health, and education.

- Justice and Historical Acknowledgment

- Official acknowledgment of past injustices (frontier violence, stolen generations, dispossession).

- Commitment to truth-telling processes (e.g. commissions, history projects).

- Measures for criminal justice reform to address overrepresentation in prisons.

- Dispute Resolution

- Independent bodies to resolve disagreements between governments and Indigenous groups.

- Legal enforceability of treaty terms (so they can’t be overturned easily).

After reading this, I trust people have a better understanding of why a treaty is essential. The fact that England never put one in place is a scar on our history, and a festering sore for many indigenous people. It is only when we put it into context that we begin to understand why it is such an enduring topic.

I hope more people understand the history of the non-treaty.

We have a new Facebook page. Please subscribe. It needs some friends.