Immigration. Who comes, how and why.

Immigration is a hot-button topic. Mention immigration, and emotions roll out. Too many, causing a housing crisis, not integrating, and increasing crime. But what are the facts? How much of a problem is immigration, and what are the alternatives?

I looked at the most recent data from the 2023-24 Migration Program and the latest ABS estimates. Before we start discussing the data, it is worth defining a few terms that sometimes get misused.

Definitions

Immigration. The action of coming to live permanently in a foreign country. The implication is that the person came legally. The Australian Government had permitted them to live in the country.

Refugee. Article 1 of the 1951 UN Refugee Convention defines a refugee as someone who “owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of [their] nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail [themself] of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of [their] former habitual residence, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.”

This leads to the concept of legal and illegal refugees. If the country where the refugee has fled accepts them, they meet the UN standard, and they are a legal refugee. If not, they are illegal refugees. The assessment may be initially undertaken by the Immigration Department, but can be appealed through the court system.

Net Overseas Migration. The number of people entering the country under a migration program, minus those who leave. It’s calculated using the “12/16 rule,” which includes people who have been, or are expected to be, in the country for 12 months or more over a 16-month period. This figure is used to estimate a country’s resident population, alongside births and deaths.

Big Picture

Now, back to the data. Australia’s 2023–24 permanent Migration Program was set at 190,000 places, with the Humanitarian Program adding another ~20,000, bringing total permanent visas granted to around 210,000. But permanent visas tell only part of the story.

The ABS statistics estimate that net overseas migration (NOM) for 2023–24 reached 446,000. NOM includes temporary migrants — international students, working holiday makers, skilled temporary workers — who, in aggregate, shape population growth far more than the permanent intake. In the same year, nearly 8 million temporary visas of various kinds were granted. The gap between the permanent intake and the much larger temporary movement is central to understanding population growth, housing pressure and workforce supply.

Migration Program

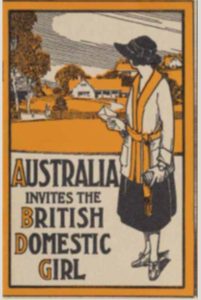

The Migration Program has three core streams:

- Skill Stream includes company-sponsored as well as people who can fill a skill shortage in Australia.

- Family Stream. It may be a partner of an Australian resident, or the family of a person already resident in Australia.

- Special Eligibility. The department’s category for unusual requests.

In 2023–24, the allocation was intentionally weighted toward skills. This is the breakdown of the 190,000 migrants:

- Skill stream: 137,100 places (72%)

- Family stream: 52,720 places (28%)

- Special Eligibility: 180 places

Skills Stream

The top-nominated occupations for employer-sponsored primary applicants were:

- Registered nurses

- Accountants

- Software and applications programmers

This pattern reflects shortages in healthcare and hospitality, as well as sustained demand for ICT professionals. Go to any nursing home, hospital or medical centre, and you will find migrants filling many of the roles.

There were almost 10,000 registered nurses among the 137,000 skilled immigrants. Accountants and Software programmers made up another 9,000. The ABS stats do not list numbers beyond the top three, but eligibility is based on need, so wherever there is a shortage in the Australian workforce, resources are sought from overseas.

Family Stream

Family visas remain a crucial but constrained part of the system. In 2023–24, the Family stream delivered 52,720 places, including:

- Partner visas (~40,500 planned places)

- Child visas (~3,000 planned places)

- Parent visas (limited and heavily oversubscribed)

Partner and child visas operate on a demand-driven level. It depends on how many Australians marry outside the country and want to bring their partner to Australia. The most extended delays are for parent visas, where waiting times stretch into many years and, in some subclasses, decades. Recent reporting has highlighted applicants dying while still in the queue.

Family reunion remains politically sensitive: it is essential for social and cultural stability among migrant communities, yet also constrained because it does not directly address workforce shortages in the same way as skilled migration.

Students.

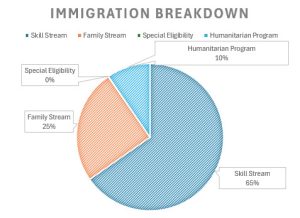

This is a breakdown of the student visas issued in 2023-24.

- In the 2023–24 program year, according to the Department of Home Affairs website, there were 376,731 student visas granted.

- These grants break down across different sectors as follows (for 2023–24):

- Higher Education: 227,230 visas granted

- Vocational Education and Training (VET): 65,616 grants

- Independent ELICOS (English-language courses): 39,020 grants

- Non-award courses: 17,663 grants

- Postgraduate Research: 12,796 grants

- School-sector: 9,778 grants

- Foreign Affairs / Defence sector visas: 4,628 grants

As you can see, the number of student visas is way higher than the number of immigration visas: 377,000 student visas and only 190,000 immigration visas.

What we need to remember is that a student visa is only for a few years. In 2024, there were 608,000 student visas held by students in Australia. This was almost double what it was during the COVID years. If the number of visas issued matched the number expiring, the overall number of students in Australia would not increase. More on that later in the article

Origin

Not surprisingly, the most immigrants come from India, followed by China and the Philippines.

Age of Immigrants

There is a problem in Australia, as in many other Western countries. The balance between old and young people is changing. Australians are having fewer children (below the replacement rate) and living longer. To summarise, the number of people supported by the health and pension systems is increasing, while the number of people paying for them through their taxes is decreasing.

The solution is to increase the number of young people through migration. Many of the nationalities who migrate to this country also tend to have more than the breakeven of 2.1 children per couple.

One of the most striking features of Australia’s immigration intake is its youth. In 2023–24:

- The median age of arrivals was 27

- The most common age (mode) was 23

This youthful profile comes primarily from international students and working holiday makers, but skilled migrants also tend to be younger than the Australian-born population.

Education level

The qualification profile of recent migrants is consistently strong. According to ABS data:

- About 69% of recent migrants hold a post-school qualification before arriving

- The largest share holds a Bachelor’s degree or higher

- Common fields include:

-

- Management and commerce

- Engineering and related technologies

- Health

- Information technology

These fields closely match the areas of most significant skill shortages in Australia. A substantial proportion of migrants initially work below their qualification level, particularly in their first few years in Australia. Qualification recognition, local experience barriers and language expectations contribute to underemployment, which represents lost economic potential both for migrants and for Australia.

The Temporary-to-Permanent Pipeline

A defining feature of Australia’s migration model is that more than half of permanent visas go to people already onshore.

In 2023–24:

- 57% of permanent migrants were already living in Australia on a temporary visa

The most common temporary “feeder” visas were:

- Student visas

- Temporary Graduate visas

- Temporary Skill Shortage (TSS) visas

To take a step back, the Government used to fund universities, but for the last half-century has cut back. When the Whitlam government assumed responsibility for all higher education funding from the states in 1974, the Commonwealth provided 90% of universities’ income. By 2010, this had fallen to about 42%, and is now closer to just 20% at major research universities.

The universities’ response was to take in more fee-paying overseas students. They needed temporary visas to study, and many decided that after three or four years in Australia, they wanted to stay.

This pipeline means that migration outcomes — numbers, demographics, and skill profiles — are heavily shaped by Australia’s temporary visa settings several years earlier. For example, large student intakes lead to larger graduate numbers, which eventually produce stronger demand for employer-sponsored and skilled independent permanent visas.

This interconnectedness is at the centre of recent policy debates over student caps, Temporary Skill Shortage reform, and recognition of overseas qualifications.

The universities want more students to come to Australia to boost their coffers. That means more demand on the government for student visas.

Net Overseas Migration

All the figures to date are about immigration. In reality, there is a lag between when an immigration visa is issued and when the person arrives in the country, or, in some cases, decides not to migrate. If we look at NOM, which is the number of arrivals (immigration + students) minus the number who left the country in 2023-24, this is the situation.

- 667,000 arrivals

- Leaving Australia. 221,000 departures

- Net Overseas Migration. 446,000

The drop in NOM (from 536,000 in 2022–23 to 446,000 in 2023–24) marks the first annual decrease in net overseas migration since post-COVID border reopenings.

Conclusion

A couple of forces drive immigration.

- An aging workforce and the need for more young people to provide taxation revenue to support pensions and health expenses.

- Universities seeking more revenue from foreign students

- Skills shortages in things like medicine, carers, IT and finance

Student visas have several repercussions, both good and bad.

- They provide a pool of cheap labour

- Their overall numbers remain unchanged unless the government allows bigger annual intakes, as the universities demand

- A proportion will apply to stay in Australia and will contribute to the Australian economy through the investment they make in their education

- The not insignificant number of 609,000 student residents in Australia dwarfs the 210,000 immigrants entering Australia in the reported period

There is no simple solution. Cut student numbers and watch the universities scream as they cut teaching jobs and research. In any case, a cut today might take three years to work its way through the system into reductions in the number of those seeking residency.

Another impact will be the number of food delivery drivers, Uber drivers, shop assistants and restaurant staff available. Shortages will drive up wages, which in turn will hit every consumer and fuel inflation.

Cut immigration, and we hurt, in particular, the health and caring environment. Hospitals, retirement villages, doctors and dentists would be in short supply. We have already squeezed the family reunion area, and many residents who want to bring family to Australia have little chance of that happening.

If we can find a way to recognise overseas qualifications, particularly in the trade sector, we might be able to allocate more resources to housing and infrastructure.

I don’t have any answers. I hope this article provides some perspective on the issue of immigration and helps you draw better conclusions of your own.